As residents of Twentynine Palms, California, we strongly oppose the development of a commercial-scale solar power plant within our city limits. This project has been proposed by the Slovakian company E-Group. Construction will begin in 2025 if permission is granted by the Twentynine Palms City Council. Here are our Top Ten reasons for opposing this bad solar project.

Top Ten Reasons

Photo of Desert Tortoise near the proposed solar plant location in 29 Palms California. From Mary Kay Sherry, 2024.

1. The solar plant would destroy Desert Tortoise habitat. Observations by local citizens document the existence of a healthy Desert Tortoise population in the same location where the solar plant would be built. See photos on this website taken by Twentynine Palms resident Mary Kay Sherry in 2024, for example.

The Desert Tortoise is an endangered species. Though it is the California state reptile, this iconic species is hurtling toward extinction (Lin, 2024). It is illegal to harm the Desert Tortoise and it is fully protected by federal law. The location that the solar developer E-Group has chosen is therefore an untenable choice. The large, reproducing population of Desert Tortoise we have in our midst is a rare treasure.

If state and federal environmental regulations protecting endangered species are respected, the E-Group project is a non-starter. However, financial motivation is a strong force. Parties standing to profit are incentivized to work around laws protecting endangered wildlife.

Note that there is no way to preserve a Desert Tortoise population whose habitat has been destroyed. Developers, including E-Group, sometimes offer a mitigation measure called translocation. Translocation involves digging up individual tortoises and bringing them to new locations. However, long-term studies show that this method is ineffective. Among the many reasons: juvenile tortoises and hatchlings are usually left behind, likely to be “crushed or buried alive by earth movers” (Haas, 2024). Also, translocated tortoises are subject to infectious disease in new locations because they lack sufficient immunities against endemic pathogens. The many stresses associated with capture and release take their toll. A few elaborate and costly translocation projects have shown some promise. But these involve expensive and innovative methods, including refraining from leveling the land (Roth, 2023a). Such efforts are far beyond the norm. Patrick Donelly, Great Basin director at the Center for Biological Diversity, put it this way: “Translocating tortoises is pointless. As far as the long-term viability of the species and the populations affected, you might as well just kill them” (Salon, 2022).

2. The solar plant would produce more frequent and severe dust storms. Natural desert soil is covered by biological crust, also sometimes called “desert glue” (Joshua Tree National Park, 2024). This is a thin layer of living and nonliving material built up by microscopic and other small organisms over time. Biological crust holds soil grains together. When the desert is bulldozed, soil-sealing biological crust is removed. Grains of silt, dust, and sand can then be easily picked up and carried by desert winds. This can turn windstorms into dust storms.

In addition, solar farms consist of thousands of solar panels arranged in large arrays on flat surfaces. The proposed site consists of rolling and sloping terrain so it would require extensive grading by bulldozing (City of Twentynine Palms, 2024). This disruption would destroy biological crust as referenced above. Further, the terrain is now covered by ancient creosote bushes and other plant life. The site would be denuded-stripped of vegetation-in the grading process. Plant roots now holding the soil in place would be destroyed. Also, bulldozing would rip apart mycorrhizae—dense webs of interconnected fungus and plant roots that also anchor soil grains in place. Bottom line: grading desert soil to build solar arrays removes biological crust as well as native plants and mycorrhizae. The net result is to loosen soil particles so that dust storms become more frequent and more severe.

Furthermore, the proposed solar site exists on a sand transport path. Sand transport paths contain soil composed of the finest (smallest) desert sediments (Flanagan, 2017b). Wind picks up fine sediments more easily than larger particles and carries them further. For this reason, sand transport paths are particularly susceptible to wind erosion and they are terrible locations for solar farms. The proposed site would increase dust storms due to the effects of grading desert soil as well as due to its location on a sand transport path.

Where would the fugitive dust blow? Mojave winds generally blow from west to east. Thus, wind-borne dust, silt and sand would blow eastward from the solar plant toward commercial and residential sections of Twentynine Palms (Flanagan, 2017a; Kobaly, 2019; Lauer et al. 2023). Residents to the immediate east of the plant, including myself (Suzanne Lyons, science educator and author of this article) would likely experience the strongest impacts. However, severe and frequent dust storms are a potential threat to our entire community.

Dust gathering as wind blows in the sand transport path where the proposed solar farm would be built. Photo from local naturalist and environmental author and researcher Pat Flanagan, 2016.

3. The power plant would damage air quality, endangering public health. The solar plant puts air quality at risk for the same reason that it promises worse dust storms: destruction of natural mechanisms that hold desert soil in place. As stated, even light winds can pick up tiny particles of unconsolidated soil and carry them into the air. The particulates pollute the air making it toxic to breathe. Asthma, other respiratory conditions, and heart disease are familiar examples of disease associated with poor air quality.

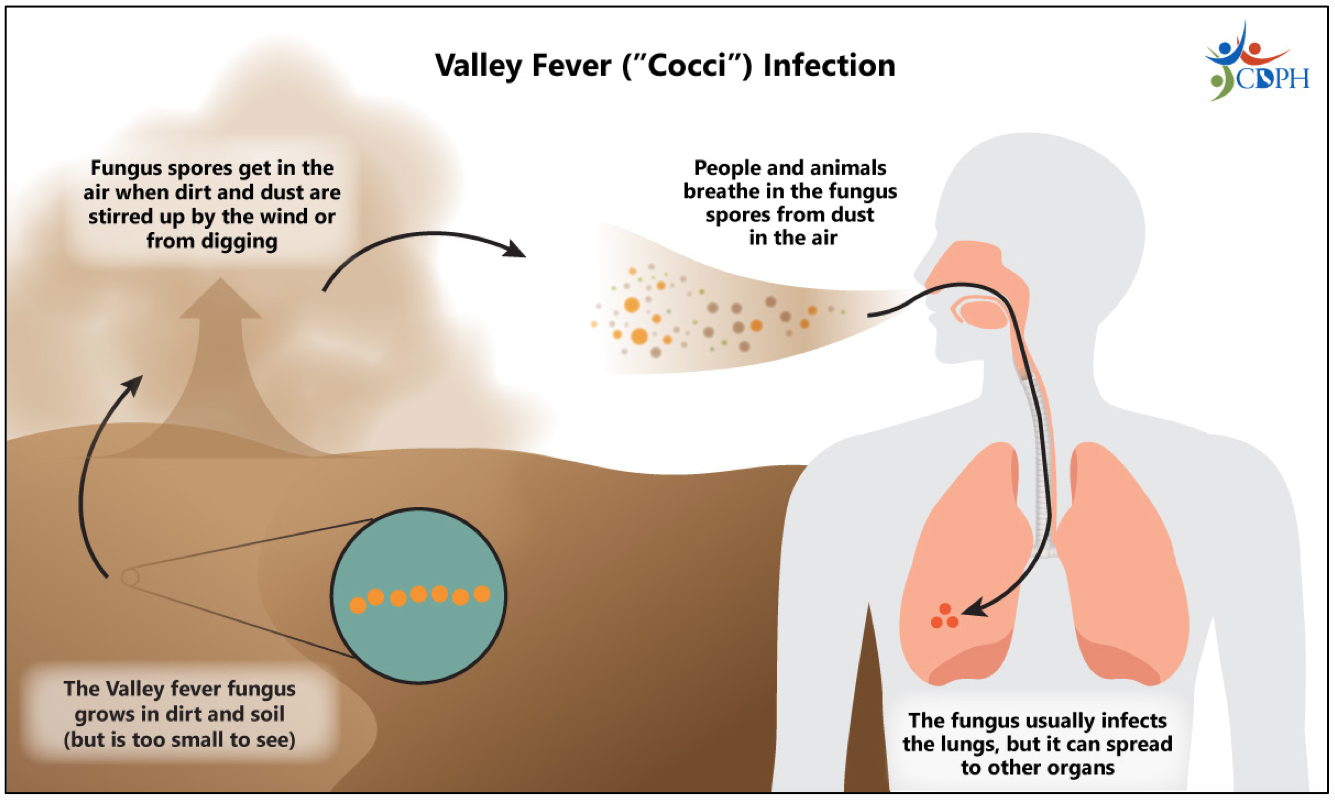

Alas, in the Mojave Desert, there is an additional disease we must protect ourselves from—Valley fever. Valley fever also goes by the names of desert rheumatism and coccidioidomycosis. It is a respiratory illness caused by pathogenic spores released by a fungus that normally lives underground in the Mojave Desert. Valley fever can be asymptomatic or cause flu-like symptoms, rashes, and fatigue. It can also lead to more serious effects when it infects the skin, bone, and brain (Lauer, English & Helton Richardson, 2023).

The incidence of Valley fever has surged dramatically in Mojave communities where large-scale solar has been developed, for example Boron. As commercial solar power has expanded, so has Valley fever. Valley fever is an environmental justice issue as well as a public health concern, disproportionately affecting lower-income residents of small, under-resourced, and politically isolated desert communities (Lauer, English & Helton Richardson, 2023).

Spoiling our air not only disrespects the public health, it violates our heritage. If you know the history of Twentynine Palms, you know that homesteaders settled here beginning in the 1920’s seeking the health benefits of pure desert air. The town was a refuge for World War I veterans whose lungs had been burned by mustard gas. How tragic and disrespectful it would be for us, the current stewards of this place, to let an ill-conceived solar farm wreck the precious desert air.

Valley fever is caused by fungus spores normally underground that are released into the air when desert soil is disturbed. California Department of Public Health 2024.

4. Destruction of a natural carbon sink that already helps protect us against climate change The current project would operate for 35 years, according to E-Group (City of Twentynine Palms, 2024). As described, native vegetation including a large amount of creosote and yucca would be removed and the soil would be broken up. The disruption would tear apart mycorrhizal networks, the ancient masses of symbiotic plants and fungi that support life and hold soil in place. What this article has not yet explained, however, is that the underground web of life securing the soil also absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It is a “carbon sink.” Undisturbed desert soil sequesters greenhouse gas from the atmosphere, protecting Earth’s atmosphere against climate change.

As a pristine desert ecosystem, the carbon-sequestering community of organisms at the power plant site has existed there for hundreds or thousands of years. Without the need for any human intervention, the living community has been steadily removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. How does this work? Desert plants absorb carbon dioxide from the air during photosynthesis. The carbon dioxide taken in undergoes numerous chemical reactions. It is converted to sugars that feed the plant itself. It is also converted to food that is delivered to the fungi that link up with the plant’s roots. Thus the carbon, which had once resided in the air as carbon dioxide, gets broken down into numerous substances that move through the carbon cycle underground. These carbon-containing substances have many uses including building the tissues of desert animals and so much more. As well, some of the sequestered carbon is transformed into deposits of the rock caliche where it is stored for many, many years. You are familiar with the white, rocky caliche if you have gardened in the desert or drilled a well.

Solar power plants must be sited very carefully. They produce electricity of course, which reduces greenhouse gas emissions that would otherwise come from burning fossil fuels. However, industrial solar power plants have a big environmental impact. They create problems as well as solve them. The best sites for solar are on previously disturbed soil. Abandoned farms on drought-damaged soil are an example (Lauer, English & Helton Richardson, 2023). Urban spaces such as rooftops and parking lots also make sense, especially if they are close to where the power will be consumed (Kobaly, 2019). There are other options too.

To be sure, solar power plants that are built in the desert can and will make a major contribution to climate preservation. However, citizens need to understand that a huge economic incentive is now driving corporations worldwide to “get in the game” of solar power development in the Mojave Desert (Petersen, 2024). Not all of these enterprises will be reputable or trustworthy. Corporations coming into our area therefore need to be carefully screened, watched closely, and held to high standards.

5. What exactly is E-Group? We’re not sure! As reported in the Desert Trumpet, E-Group has very little online presence. It has a small website: https://www.e-group.sk/en/ It is not an American company. E-Group was founded in 2008 in Slovakia and is listed on the Czech stock exchange. The website says that E-Group has been doing business in the U.S. since only 2019. As such, E-Group does not have an established reputation or a track record that can be easily verified.

In fact, E-Group’s website gives the impression that the company is an investment firm rather than an organization that completes engineering projects in a hands-on manner. It says that its “annual investments” equal $140,000,000 USD and that “total assets under management” are $1.2 billion USD. Further, the website says, “E-Group is a group of companies whose primary interest is in energy investments. Key centres of operation are in the EU and Ukraine, with projects also under operation in the U.S.A.” It goes on to describe its business model: “The final phase of every business cycle is an M&A process in line with our business strategy.” Note that M&A is a business term that stands for “mergers and acquisitions”—a transfer of ownership. E-Group has represented itself to our community as the developer of the proposed plant, but the site lists no employees other than a single CEO. Does this company have the capacity and engineering expertise to build and operate a complex power plant?

Is it possible that E-Group plans to develop the plant then sell it to a large energy corporation, such as Duke Energy, which operates the Highlander 1 solar plant on Lear Road (Talley-Jones, 2024)? Alternatively, is it E-Group’s hope to obtain permits from the City then sell them to a company that would both develop and operate a solar plant?

Another unclear aspect of E Group is where it does business. Although the website states that it has “projects also under operation in the U.S.A.”, it does not provide details. What specific projects has E-Group completed here since 2019? Where are they? What was the nature of the work that E-Group conducted or oversaw? Were previous projects successful? Were they failures? We need to know.

E-Group does not own the land where the proposed plant would be built. It leases the acreage from Proactive Properties LLC, a firm owned by real estate investor/radiologist George Mulopulos who resides in Las Vegas.

There has been little sign of any employees of E-Group. E-Group’s interactions with the City of Twentynine Palms have been mainly conducted through an attorney named Robert M. Smith. Smith is a staff lawyer employed by K&L Gates, one of the world’s largest international law firms.

With its vague website, lack of a track record, scant evidence of employees, foreign base of operations, and lack of clarity regarding the nature of its business, E-Group is truly shrouded in mystery. Is it reasonable for the residents of Twentynine Palms to place our future in the hands of a company that we know so little about?

6. Loss of scenic vistas, desert ambience, and open space Words cannot express how beautiful the undeveloped site is. Go out to the end of Samarkand and see for yourself. The sweeping desert floor is covered with desert plants. Its wavy surface is rhythmic and sea-like. Wildlife, not just our venerable Desert Tortoise, but other species including coyotes, jack rabbits, road runners, doves, myriad lace-like insects with intricate forms, and burrowing owls are among the animals that live here. In the evening, look westward. Massive Mount San Gorgonio and Goat Mountain, an iconic mesa silhouette, stand among sloping mountain peaks and valleys that rim the horizon. This is a place to watch the sunset like no other. When darkness falls, the vast open space is transformed to black velvet. The moon and stars hang like shiny ornaments in the encompassing sky. On some nights, you can hear owls hoot and coyotes howl. The place feels sacred.

So much of our natural environment has been transformed by human development. Polluted air, noise, bright lights, commercialization, ruination of scenic vistas—these are all-too common results of industrialization. While the comforts of modern life are cherished for the good things they provide, human beings also need nature. Our mental and physical health depend on it. This is why contemporary city planning often involves incorporating green space. The targeted site offers many of the benefits of green space which would be erased. For anyone who ventures down Samarkand Drive, the site provides a spectacular vista. For homeowners to the east and south, it is an oasis of peace and quiet—a buffer against the stresses of urbanization. Astonishingly, though, the site is just a 4-minute drive from the nearest supermarket and shopping mall. For everyone driving along Highway 62 and Two Mile Road, the site is part of a natural expanse that provides a delightful visual break from dense development. It reminds you that you are still in the desert.

The proposed solar power plant would occupy approximately 200 acres and sit on about 500 acres of land that E Group would control (City of Twentynine Palms, 2024). There would be 720 ground-mounted photovoltaic (PV) arrays, each 104 feet wide and 252 feet long, separated by service drives. In total, 160,000 solar panels would be installed, generating glare that poses a hazard to migrating birds. Power would be routed to the Carodean substation located on the south side of Two Mile Road. During construction, noise, dust generation, and traffic would be hard for nearby residents to bear. When the construction phase ends, glare from the panels and noise from transformers, inverters, and other sources would persist. The City of Twentynine Palms has determined that the development could impact local aesthetics, air quality, geology and soils, greenhouse gas emissions, and biological resources, and more so that an environmental impact report (EIR) is required. It is crucial that the EIR is conducted by third parties that do not have financial interest in the plant and are therefore not biased. A proper EIR should keep our environment healthy and beautiful.

Photo of proposed power plant site as it exists now in 2024. Homeowner Peter Lang appreciates the view, as do many other neighbors and visitors.

7. Lifting the existing ban on solar development in the City of Twentynine Palms The City’s Development Code bans utility-scale solar farms. (See: 19.18.030 Allowed Uses and Permit Requirements.) The ban was put in place in 2012 shortly after the Highlander 1 Solar Field became operational (Talley-Jones, 2024). The Planning Commission stated that:

Commercial Solar Fields can be shown to have direct, adverse impacts to the aesthetic quality of the desert vistas the community now enjoys, deleterious effects to the tourist industry that the community depends on, potential adverse impacts to property values for the properties adjoining or surrounding such facilities, and potential serious impacts to the biologic, cultural and social resources to our community.

-Twentynine Palms Planning Commission 2012

The impacts from the couple of exiting solar energy plants in Twentynine Palms that led to this ban have only increased since the time this ban was put in place. The ban is therefore even more necessary now than it was before. In fact, other industrial-scale plants have been constructed in Morongo Basin that also affect our air quality by increasing fugitive dust (Flanagan, 2017a). Air quality and dust storms are a growing problem. The Twentynine Palms ban on utility-scale solar power plant construction exists for good reason. It’s more important now than before. The City should not bow to the pressure campaign waged by E-Group which risks the welfare of our community. (See Number 9 on this list to learn more about E-Group’s pressure campaign.) now than before. The City should not bow to the pressure campaign waged by E-Group which risks the welfare of our community. (See Number 9 on this list to learn more about E-Group’s pressure campaign.)

8. Economic impacts What would the economic impact of the plant be? That is an overly broad question. A better question is: who makes money, who loses money, and do the profits justify the costs?

There are a few clear winners and losers. Homeowners living near the plant would lose money due to declining property values. The Planning Commission’s statement above verifies this by citing “potential adverse impacts to property values for the properties adjoining or surrounding these properties.” Short term rentals nearby would also directly lose money. Other businesses that serve the tourist industry would lose money too because the plant would be unsightly, would be close to town, and would increase fugitive dust. Dusty windy days are already a problem in our location for tourists; the plant would make that worse.

Who gains financially? E-Group and its overseas shareholders, mainly. Proactive Properties LLC, owner of the parcels, also directly benefits. Electricity generated at the site would be sold to Southern California Edison (SCE) for distribution through its grid. Depending on the price SCE pays but based on current estimates, the developers and landowners could receive $1,600,000 or more per year from the plant’s operation. Note that project costs are not factored into this estimate because that information was not provided to the Desert Trumpet, (local news provider) in its public information request to the City. Alternatively, E-Group and the landowner could sell the project to an energy corporation like Duke Energy, which acquired the Highlander 1 Solar Farm on Lear Road from its developer Solar World in 2013 (Talley-Jones, 2024). In this scenario, E-Group and Proactive Properties could collect their profits without doing the ongoing work of operating the plant.

E-Group did not have to chose the location it decided upon for its plant. Other desert locations are available. The chosen site was financially enticing due to its close proximity to the existing Carodean substation. This proximity saves E-Group money by reducing the cost of connecting its plant to the electrical grid. Unfortunately, while the chosen site maximizes profits to investors it also maximizes the harms done to the Desert Tortoise, the neighborhood, and the town at large.

What about jobs? Would the plant provide good jobs to fuel the local economy? No. As the Desert Trumpet reports: E-group attorney Robert Smith has stated that the facility would bring up to 300 jobs over the 35-year lifespan of the project. But 200 of these jobs would only last one year, during the construction phase. Maintenance and security would be done remotely. Robots would clean the panels with water trucked in from elsewhere during what they describe as “wind events.” “It’s not a lot of jobs” Smith admitted at a public meeting March 20, 2024 (Talley-Jones, 2024).

There is an economic incentive for the City because it would receive income from taxes and fees. A “community benefits package” is also involved. That is currently under negotiation, but Smith has said this about it: “We’re still in negotiations with the City as to what that community package will look like. It’s going to include a local solar fee, which is going to go directly into the General Fund to fund whatever projects City Council and Planning Commission determine are appropriate.” (Talley-Jones, 2024).

In this arrangement, E-Group would send payments to City officials who would decide how to spend them. How should the public react to this idea? While City officials and the public enjoy good relations now, the funding arrangement E-Group came up with engenders division that would negatively affect us. It nurtures the appearance of cronyism by paying City officials with no strings attached. It leaves the community out of the loop. It certainly provides cold comfort to solar farm neighbors. These community members stand to lose the peaceful enjoyment of their homes along with many thousands of dollars in slashed property values, with no compensation.

9. Rushed timeline and pressure campaign E-Group has notified the City of Twentynine Palms that it plans to begin construction on the plant in 2025 and commence operation in 2026 (City of Twentynine Palms, 2024). This is a very short timeline. It requires that the environmental review process, which includes both an EIR and a CEQA, be accomplished over the next 18 months. This does not give enough time for adequate environmental studies to be done by vetted, independent professionals. The short timeline also does not give the public enough time to assess the reports and respond. Even without the results of the environmental studies, E-Group is pushing the City to begin the rezoning required to lift the ban and permit the project. Citizens do not have enough time to learn about the project let alone have their questions answered.

In addition to the accelerated timeframe, E-Group is pursuing a pressure campaign on our community by making us believe we have no choice but to submit to their demands. It wants us to think that the State of California will permit the E-Group plant no matter what. Further, they threaten to reduce their willingness to negotiate with our community if we do not permit the plant before they seek approval from the state.

Attorney Robert Smith acknowledged the City’s moratorium on solar development in a letter dated May 17, 2023. Smith’s letter says: “In the event that the City elects to maintain its current moratorium and not work with E- Group, E-Group will pursue approvals through the permitting process recently established through Assembly Bill 205, which intends to facilitate the approval of renewable energy projects by the State without any local approval. If approved by the State, the City will have far less control over project design and conditions of approval and would receive substantially less in public benefits. While this is not E-Group’s preferred outcome, it is willing to vigorously pursue this route if needed” (Talley-Jones, 2024).

Thus, E-Group has threatened to circumvent local authorities if they do not cede to its demands on its super-fast schedule. Accordingly, citizens who have learned of the project have expressed feeling “bullied.” They have described the project as a “shakedown” (Schauppner, 2023). Based on public comments, the majority of public opinion is clearly opposed to development. While no one really wants the plant, some have said they feel trapped into compliance. They say we better acquiesce to E-Group so that we don’t lose negotiating power with them. One can imagine that City officials may also be feeling the pressure.

Does E-Group have all the power it claims? Are we really powerless? Fortunately, we citizens and elected officials do have the power to decide whether this bad solar plant really comes to our town. First, AB 205 does not assure approval from the State of California. This must be emphasized. Secondly, even if the State of California were to permit the plant, AB 205 does not allow developers to cut communities off from negotiation or benefits. Let’s examine each of these points.

First, the E-Group power plant would likely not qualify for approval from the state. Why? Under AB 205, the State of California would do a thorough environmental review. Scientists and engineers who are not on E-Group’s payroll would do the assessment. As explained, there is a healthy, reproducing Desert Tortoise population in the site area—an indisputable fact. The Desert Tortoise is legally protected by the Endangered Species act. E-Group’s proposal should fail the environmental review due to that alone. The project’s other serious environmental impacts, especially those related to dust and public health, would also be evaluated carefully and would likely stop the project.

Second, E-Group could not punish the City of Twentynine Palms for refusing approval. In the perhaps unlikely chance that the project qualifies for approval under AB 205, the State of California would require E-Group to negotiate with the City and provide enforceable benefits. Specifically, to qualify under AB 205, projects must:

- Demonstrate a net positive economic benefit to the local government that would have had authority over the project, such as employment growth, increased taxes, assistance for schools or public safety services or some other economic benefit.

- Enter into an enforceable community benefits agreement with one or more community-based organizations, such as labor unions, environmental groups, local government, social justice advocates or California Native American tribes. Examples of community benefits include job training, high road training partnerships, assistance for parks or playgrounds, urban greening, paving and bike lane projects, public safety projects or other benefits (Mudge, Weiner & Hull, 2024).

And so, there is nothing to lose and nothing to fear if the City of Twentynine Palms takes its time and fully exercises its protective role. There is everything to gain by being careful.

10. Opening the floodgates In order for E-Group’s project to be developed, the City of Twentynine Palms would need to reverse itself and rescind its current ban on commercial solar (City of Twentynine Palms, 2023). If the City takes this step, it will set a precedent and alter zoning regulations that protect us now. Additional developers would see that there is little to stop them from developing here too. From their perspective, why not seize the opportunity to construct even more ugly, polluting industrial solar plants in Twentynine Palms City limits close to our neighborhoods? It’s open season!

Commercial solar plants are too big and impactful to make good next-door neighbors in community settings. We are not an isolated desert region with a sparse population. We are a growing, vibrant community with a bright economic future. We have a legacy to protect, an ambience that residents and tourists love, and the endangered Desert Tortoise in our midst. We should not open up our beloved hometown to commercial solar exploitation.

References

1. California Department of Public Health (2024.) Valley Fever Awareness and Outreach Toolkit https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/ValleyFeverOutreachToolkit.aspx

2. City of Twentynine Palms. (2024). Notice of Preparation and Initial Study. https://www.ci.twentynine-palms.ca.us/vertical/sites/%7BAE145833-008D-4FBA-AEC7-7D0EBD90E334%7D/uploads/Revised_29_Palms_Solar_IS-NOP_2.20.241.pdf

3. Farah, T. (2022) California desert tortoises are hurtling toward extinction. Saving them won’t be easy. Salon. https://www.salon.com/2022/12/12/california-desert-tortoises-are-hurtling-toward-extinction-saving-them-wont-be-easy/

4. Flanagan, P. (March 17, 2017). The perfect (dust storm)—fugitive dust and the Morongo basin community of Desert Heights. The Desert Report. https://desertreport.org/the-perfect-dust-storm-fugitive-dust-and-the-morongo-basin-community-of-desert-heights/

5. Flanagan, P. (July 20, 2017). Sand Transport Paths in the Mojave Desert. Morongo Basin Advisory Council. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/mbca/pages/907/attachments/original/1501211030/LV_MAC_Presentation.pdf?1501211030

6. Haas, G. (2023). Desert tortoise habitat cited in request to kill solar project south of Parhump. 8 News Now.com. https://www.8newsnow.com/news/local-news/desert-tortoise-habitat-cited-in-request-to-kill-solar-project-south-of-pahrump/

7. Joshua Tree National Park. (2024). Cryptobiotic Crusts. https://www.nps.gov/jotr/learn/nature/cryptocrusts.htm

8. Kobaly, Robin. (2019). The Desert Underground, Exposing a Valuable Hidden World Under Our Feet. Summerhill Tree Institute.

9. Lauer, A., English D., Helton Richardson, M., & You, S. (2023). How “green energy” is threatening biodiversity, human health, and environmental justice: An example from the Mojave Desert, California. Sustainable Environment, 9(1). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/27658511.2023.2192087

10. Lin, S. (2024). Mojave Desert tortoise officially joins California’s endangered list. The Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-04-20/mohave-desert-tortoise-joins-californias-endangered-list

11. Mudge, Anne E., Weiner, Peter H., and Hull, Robert C. (2024) California Opens New Pathway for Renewable Energy Projects. Cox Castle (Law Firm). https://www.coxcastle.com/publication-california-opens-new-permitting-pathway-for-renewable-energy-projects

12. Petersen, M. (2024). Solar project to destroy thousands of Joshua trees in the Mojave Desert. The Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2024-05-31/solar-project-to-destroy-thousands-of-joshua-trees

13. Roth, S. (2019). California’s San Bernardino County slams the brakes on big solar projects. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-san-bernardino-solar-renewable-energy-20190228-story.html

14. Roth, S. (2023). Solar sprawl is tearing up the Mojave Desert. Is there a better way? Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2023-06-27/solar-panels-could-save-california-but-they-hurt-the-desert?utm_source=yahoo&utm_medium=promo_module&utm_campaign=rss_feed

15. Schauppner, K. (2023). Sounds like a shakedown: Company may force 29 Palms to accept a solar farm. The Desert Trail. https://www.hidesertstar.com/deserttrail/sounds-like-a-shakedown-company-may-force-29-palms-to-accept-solar-farm/article_a37852be-ffde-11ed-b470-2f26bfbb6dc8.html

16. Talley-Jones, K. (2024). 29Palms Solar Project: Who Benefits? The Desert Trumpet. https://www.deserttrumpet.org/p/29palms-solar-project-who-benefits

17. 4. Wainwright, O. (2023). How solar farms took over the California desert: “An oasis has become a dead sea.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/may/21/solar-farms-energy-power-california-mojave-desert